What Are Projective Tests?

If you think you know what projective tests are, you may only know half the story.

No matter how much you’ve heard about projective tests, they are not what you think they are.

Projective tests are a target for misinformation. Whenever we have new calls with prospective clients, we are often confronted with a number of misconceptions. The reason for this post is to provide you with an informed approach on frequently used misconceptions. The bottom line is, no matter how much you’ve heard about projective tests, they are not what you think they are.

To most people—whether in academia or not—the word projection is linked to Freud’s theory of defense mechanisms. Consequently, most people think that projective methods have psychoanalytic foundations. However, “projective methods” are based on a generalized mechanism of projection, where internal states influence perceptions of the outer world (Lindzey, 1961, p. 31). Some of the most famous projective methods (e.g., Rorschach’s Inkblot Test) were created entirely separate from the rise of the psychoanalytic movement.

Misconception #1—projective methods are based on psychoanalytic principles.

Truth #1—With Frank’s 1939 paper on projective methods, they have more to do with Gestalt psychology than with psychoanalytic psychology.

Gardner Lindzey, former president of the American Psychological Association, delineated the tangled history of psychoanalysis and projective techniques in the following passage:

“...if we remember what has already been said about the dual use of the term projection in the hands of Freud, it becomes clear that the broader usage, what we have called generalized projection, is apparently the same as the process that Frank (1939) had in mind. This usage would embrace virtually all of the tests that are commonly considered to be projective devices. Consequently, on historical grounds alone, there appears to be no basis for insisting that our definition of projectives techniques involve a process identical with, or very familiar similar, to that involved in classic projection.” (Lindzey, 1961, p. 38).

This is important for two reasons. For one, the gradual decline of projective methods can be attributed to, in part, the decline in favoritism of psychoanalysis. As Freud fell out of favor, so did the tests. This suggests that there could be a lot more we can innovate and develop around projective tests. They didn’t fall out of favor because they didn’t work, they fell out of favor because they were associated with “the wrong crowd”. Therefore, those of us at Inkblot Analytics have “picked up the baton”, so to speak” and are continuing to further projective science.

Psychologists Donald Viglione and Bridget Rivera (2003) addressed the major misconceptions of projective tests in their chapter, Assessing personality and psychopathology with projective methods, by which the four misconceptions below are inspired. In their chapter. Viglione & Rivera (2003) highlight the number of misconceptions that stem from the projective metaphors used casually in conversation.

Misconception #2—projective tests are x-rays of the mind (Viglione & Rivera, 2003, p. 534).

Truth #2—projective tests enable the participant to actively construct meanings that reveal “how” people see the world.

There is a popular idea that projective tests are like an x-ray; a relatively passive imaging test. It’s an eye-grabbing metaphor that was originally championed by famed Rorschach psychologist Bruno Klopfer. However, this metaphor does more harm than good.

X-rays are a “one size fits all” technique. You use them for any problem related to bones. But this is not the case for projective methods. You cannot use the same projective test for just any research related to personality. This is why in a previous post we reviewed the various classifications of projective methods. There are many kinds of projective methods, each one fitting slightly different research objectives.

You need to stay still and passive when taking an x-ray, as motion blurs the image. Unlike an x-ray, projective tests are an active process of choice and ordering. Their techniques focus on the personality at work creating meaning in the ambiguous situation around them. This activity is key.

Projective techniques are a psychological approach that aims to capture how personality actively constructs meaning in ambiguous test material. They provide a dynamic and constructive view of personality that is alternative to static views of personality.

However, the goal of projective tests—to observe the dynamic nature of personality in real-time—is often conflated with the thought that all projective tests do the same thing.

Misconception #3—all projective tests are the same.

Truth #3—Projective tests are unequivocally diverse.

Despite this misconception, projective tests are unequivocally diverse. They differ in their goals, the materials they use, and the way they interpret results. For example, Lindsey’s taxonomy delineates five different types of responses that the array of projective tests can elicit. Associative tests (like Jung’s word association) produce reflexive, top of mind connections to a stimulus. Ex: What’s the first word you think of when you see the term ‘love’? Completion tests (like the sentence completion test) require someone to fill in the blanks in an incomplete sentence. Ex: When buying shower soap, I always shop _____. Constructive tests allow for the creation of a narrative (like the thematic apperception test) to depict how a certain character in the stimulus story would act, allowing the respondent to project their feelings onto that character. It’s more of a third person projection exercise, than a direct claim about the respondent. Ex: You view a picture of two men working on a car. One man is hard at work trying to fix a leak (without any luck so far) while the other seems perplexed and in deep thought. You would be asked: Write a story about “what might be going on here?” In choice ordering tests (like the picture arrangement test) the participant ranks, or creates a priority list, of given stimuli. Ex: Here’s a list of the same 5 household products from different Brands, rank which you are most likely to buy if money were not an issue. Finally, expressive tests (like collage) are used to reveal personality through the ways that the material is organized. Ex: construct a collage from the following magazines about “what family means to you.” Place the more important images towards the center of the collage, and the less important images towards the edges.

Many people have two core beliefs about projective tests.

In line with Misconception #1, if projective tests stemmed from psychoanalysis, and because psychoanalysis is viewed as outdated pseudoscience--according to the general public and within some academic circles--then it follows that projective tests are also pseudo-science.

This image of projective tests as pseudo-science is bolstered by the fact many individuals who don’t know the full history of projective methods believe that these tests have no process for administration of the test, and just “wing it.” Consequently, the misconception is that:

Misconception #4—projective tests are a form of armchair psychology.

Truth #4—projective tests have a specific set of instructions for administration to keep the elicited results comparable.

Take the three most famous projective tests—Jung’s word association, Rorschach’s inkblot, and Murray’s thematic apperception—for example. Each test has a framework for the creation and presentation of the test materials, the instructions given to the subject, and the measurement of in-test behavior. Interpretation is another story. Tests were commonly conducted multiple times in a single session. The results were recorded, refined, and innovated.

Projective tests were not created by armchair psychologists. They were methodically developed for use by qualified individuals (Verma, 2000). Though the rigor at which practitioners and researchers adhere to these standards was and still remains a debated, distressed topic (Lilienfeld et al., 2000).

Viglione and Rivera wrote, “without pause, many American psychologists categorize tests according to the traditional projective-objective dichotomy,” (p. 532, 2003).

These words—projective and objective—carry certain connotations.

Today, the term objective is generally applied to tests where the subject responds to a limited set of standardized stimuli with a definitive right answer, while projective tests are those that demand open-responses with no right or wrong answers. The “objectiveness” and “subjectiveness” most heavily weighs on how the researcher scores and analyzes the data.

An example of an objective test would be the MMPI. This test has items with “True” or “False” questions, and each question is said to measure a particular trait. It can be classified as objective in the sense that test items have predetermined answers, thus the scoring is objective (Floyd 2021). There is (in theory) no insertion of bias in the way the answers are scored/analyzed.

On the other hand, the Rorschach involves the presentation of the inkblot, and an open-ended response to the question “What might this be?” (Rorschach et al., 1942, p. 16). While the answers are still scored, they are not scored against right or wrong answers, just different types of answers. The data that results is more ambiguous, and therefore the interpretation of the result is subjective. This leads us to misconception #5:

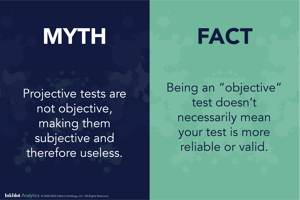

Misconception #5—projective tests are not objective, making them subjective and therefore useless.

Truth #5—Being an “objective” test doesn’t necessarily mean your test is more reliable or valid.

Just because a test is objective, does not free it from ambiguity, bias, or scoring error. There are elements of ambiguity found in the MMPI--this is why the test goes through multiple versions in which it will update its items to be more precise. For example, Viglione & Rivera credited Meehl (1945) for pointing out that qualifiers like “once in a while” are ambiguous—they could serve to mean an occurrence at the daily, weekly, or monthly level (Viglione & Rivera, 2003, p. 532). Arguments can be about the salience and ecological validity of objective tests that make them considerably subjective. For example, a true-false paradigm invites the participant to provide a subjective view of themselves or how they want to portray themselves to others (Mihura 2018).

Realistically, many psychological tests contain objective and subjective elements. As suggested by psychologists Gregory Meyer and John Kurtz, it may be time to “retire” the strict dichotomy of objective versus subjective (p. 223, 2006).

In a way, the misconceptions about projective tests speak to their biggest strengths. Constant scrutiny has not stamped out the practice, rather it’s still alive and kicking. For those of us at Inkblot Analytics, we make sure our innovations in projective testing have addressed factors like reliability and validity—things that previously lent their hand to misconceptions. It is certain that any projective method we have today has an answer to all misconceptions.

References:

Floyd, A. E., & Gupta, V. (2021). Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

Gacono, C. B., & Evans, F. B. (2008). The handbook of forensic Rorschach assessment. (N. Kaser-Boyd & L. A. Gacono, Collaborators). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Lilienfeld, S. O., Wood, J. M., & Garb, H. N. (2000). The Scientific Status of Projective Techniques. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 1(2), 27–66

Lindzey, G. (1961). Projective techniques and cross-cultural research. Appleton-Century-Crofts. 31-38.

Macfarlane, J.W. (1942) Problems of validation inherent in projective methods. Amer. J. Orthopsychiatry.12.

Meehl, P. E. (1980), [1945]. The dynamics of “structured” personality tests. In W. G. Dahlstrom and L. Dahlstrom (Eds.), Basic readings on the MMPI: A new selection on personality measurement. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Meloy, Reid, Hansen, Trace, & Weiner, Irving. (1997) Authority of the Rorschach: Legal Citations During the Past 50 Years, Journal of Personality Assessment, 69:1, 53-62.

Meyer, G.J., & Kurtz, J. E. (2006). Advancing Personality Assessment Terminology: Time to Retire "Objective" and "Projective" As Personality Test Descriptors [Editorial]. Journal of Personality Assessment, 87(3), 223–225.

Mihura J.L., Meadows E.A. (2018) Projective Tests. In: Zeigler-Hill V., Shackelford T. (eds) Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Springer, Cham.

Rapaport, D. (1942). Principles underlying projective techniques. Character & Personality; A Quarterly for Psychodiagnostic & Allied Studies, 10, 213–219

Rorschach, H., Lemkau, P., Kronenberg, B. (1942). Psychodiagnostics : a diagnostic test based on perception, including Rorschach's paper. The application of the form interpretation test (published posthumously by Dr. Emil Oberholzer). Berne, Switzerland: H. Huber; New York: Grune & Stratton.

Verma, S K. (2000). SIS Journal of Projective Psychology & Mental Health; Chandigarh Vol. 7, Iss. 1, 71-73.

Viglione, D. J., & Rivera, B. (2003). Assessing personality and psychopathology with projective methods. In J. R. Graham & J. A. Naglieri (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Assessment psychology, Vol. 10, pp. 531–552). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

If you think you know what projective tests are, you may only know half the story.

It’s no longer enough to know where people are, how old they are, and what type of job they hold; you need to know about what they like and how they...

A hallmark of projective techniques is the relatively ambiguous stimulus used to elicit uninhibited psychological data.

Be the first to know about new psychological insights that can help you optimize customer touchpoints and drive business growth.