Sensation and Perception Are Fundamental to Consumer Behavior

Today, marketing and advertising are as much an art as they are a science.

We live in a world that’s over-saturated by advertising.

We live in a world that’s over-saturated by advertising. Next time you are in the city, take a look at the diversity of billboards, retail pop-ups, vehicle stickers, and video displays. It can feel like there are more ads than real estate, or even nature!

Even if you don’t live near a big city, computers and mobile devices have created another universe for advertising: banners, social media, natives, re-targeting, and new methods will continue to pop-up in the march that is often dubbed ‘innovation’ or ‘progress.’

The results are double-edged: while it is easier than ever to target a consumer, the sheer volume of ads make it more difficult to stand out. Which leads us to the first burning question:

The short answer is, they have to be noticeable at least 50% of the time. In the 1860s, experimental psychologist and physicist Gustav Fechner innovated a way to measure changes in sensation (Fechner, 1860, 1912). He called the new field psychophysics, which formulated the relationship between the intensity of a stimulus and the resulting sensation. Fechner elaborated a few important principles about sensory perception. The foundational rule is called an absolute threshold.

An absolute threshold is the minimum amount of energy needed from a stimulus (e.g., an ad) to produce sensation at least 50% of the time (or, above chance).

With this threshold, Fechner alluded to the fact that a stimulus (e.g., an ad) can either become detectable or remain invisible to a person. While the name might suggest an ideal fixed value for generating sensations, it actually changes based on the context and the sense(s) targeted.

Take food advertising for example. A recent study added to a prior body of knowledge that multisensory ads perform better for food advertising, discovering that multisensory advertising has different effects on taste perceptions depending on whether the food displayed in the ad is healthy or unhealthy. While ads appealing to multiple senses are more effective for unhealthy foods, the new study discovered that ads focusing on a single sense performed better for healthy foods (Elder and Krishna, 2017, Roose and Mulier, 2020). Interestingly, the study on healthy foods reported that the effect for single sense ads performed well for verbal (i.e., written copy) and visual (i.e., pictures of food), showing that the two senses are rich in imagery for shaping food perceptions.

On the lower end of the threshold, when the stimulus cannot produce a sensation, the ad never even existed to the viewer. For visual stimuli, this is called sensory unawareness, where the stimulus fails to reach levels of awareness (Diano et. al., 2017). It can be a result of too little viewing time, or the fact that the ad was generally uninteresting. Therefore, if an ad cannot make an appearance in the viewer’s sensational registry at least half of the time, then the content isn’t passing engagement levels on the absolute threshold. Viewers need a fair chance to get a good look at it, but a pronounced ad with proper air-time is not always enough. A product needs to stand apart from the others. Which leads us to burning question number two:

Fechner also developed a second principle called the differential threshold. This value helped answer a key question: When we become aware of a sensation, how much does the stimulus need to change to detect a difference in sensation?

A differential threshold is the minimum amount of change needed in a stimulus’ energy (e.g., an ad’s audio volume) to enable detection of the change in sensation at least 50% of the time (or above chance).

Advertisers call this just noticeable difference, or JND thresholds. Imagine that an advertiser shows you a video that is seemingly muted. The advertiser asks you to report when you notice a difference in the ad’s volume. After two increases in volume, you don’t report any noticeable difference. So the advertiser cranks up the volume one more notch and at this moment, you say that you’ve heard the sound. In this scenario, your JND is three notches on the volume knob. So the advertiser keeps on going, cranking up the volume until you report no noticeable change. Now they’ve reached the upper limit of the threshold, where the stimulus becomes so intense that any magnifications cannot be noticed. JNDs are a simple concept that can be applied to a creative’s audio, color, sound, and messaging, to then be crafted into powerful marketing tactics.

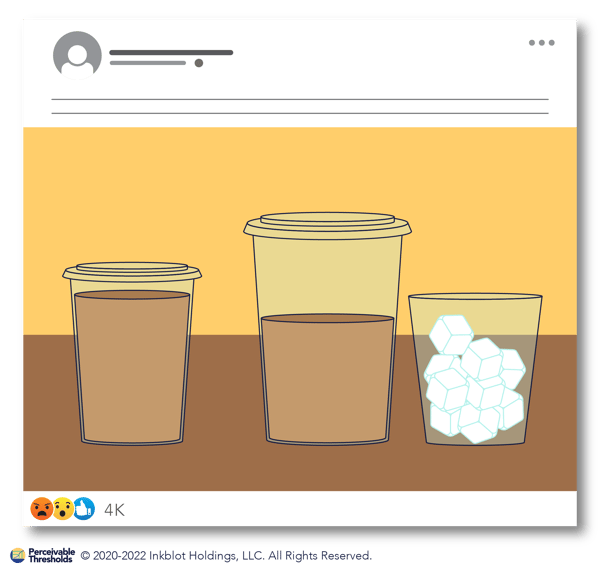

Imagine that you go to your favorite coffee shop and ask for two coffees: one medium iced coffee for your friend and one small cold brew for you. When you get home, your friend says that they don’t want any ice, so you pour it out, and transfer the coffee to a glass from your cupboard. Then you do the same to your cold brew, so you can match with your friend. When you sit down and compare your coffee cups, you see that there’s the same amount of coffee in each. Without the experiment, there’s no way you’d have noticed that the cups of coffee were actually the same amount of liquid.

Advertisers can use JND tactics to either decrease noticeability of negative aspects of a product (like that you are paying for ice, or perhaps a decrease in the quality of a product), or to highlight positive aspects of a product, like pointing out the bigger and better version of their newest line. All things considered, JNDs might be able to make a quick buck, but the risks can be disastrous in the modern world of social media. An online marketing study found that even though only a small percentage of consumers (say 1%) might discover a JND, social media allows them to disperse the information to a larger audience, making it noticeable to all (Vojtko, 2014).

It’s important for a brand to stand out, and JNDs can provide you with a roadmap for disguising the bad and the ugly while spotlighting the good. However, the rewards come with risks. If you’re using JNDs to bring an audience’s attention to a slogan, product, or certain creative so that its features pass the differential threshold, then JNDs can be a scientific business tool. However, the use of JNDs to craft a message that is misleading is simply unethical.

And yet, in a market where there are dozens, if not hundreds, of brands of foods, waters, and tech goods, the motivation to stand out is real. Consumers are getting more privy to the tricks of the trade, and quickly filter out what they don’t find relevant or interesting. Even more, many younger consumers don’t like hard sells. Brands have become very creative in their approach to capture attention, leading to ad campaigns like the Doritos anti-ad that was brandless and logoless. They connected with Gen Z’s personality in a multi-skilled way, adapting their content to the demographic and psychographic profiles of the audience. Innovate or evaporate, the old saying goes. Which leads us to the final burning question:

When we interact with a new environment the nervous system can adapt to sensory inputs that are continually exposed. For example, our eyes can adjust to a light or dark room (Webster 2012). This is called sensory adaptation.

Sensory adaptation is the brain’s ability to monitor and adjust to the barrage of stimuli that is the world around us. Sensory adaptation significantly influences our awareness and perceptual experiences by allowing attention to be directed elsewhere (Zamboni et. al., 2021).

For advertisers, that means a few things. First, consumers adapt to ads and become less sensitive to them over time. Second, creatives need designs that can overcome sensory adaptation without floating out of relevancy. That means that the ad needs to change its signal enough to boost sensory engagement.

One way to do this is by taking any static logotypes and adding some dynamic imagery, where a still frame can be perceived as if it is in motion. A static message goes in one ear and out the other. Dynamic images have been shown to capture more engagement—which lead to more positive attitudes—for brands when compared to static images (Cian et. al., 2014).

Another way is to add music that fits the scene. A good song can transport someone into the ad and unlock their emotions. Who could forget Jet’s “Are you gonna be my girl” featuring in the Apple iPod commercials with the dancing silhouettes? Research shows that tastefully selected music can improve how someone processes an ad’s message, as well as their attitude towards the brand (Krishna et. al., 2016). This is a perfect example of how sensory adaptation can influence our experiences. Music provides the perfect opportunity to prevent someone from tuning out.

If you are still curious to learn more about these sensory thresholds—or simply have more burning questions about how to optimize your ad creatives—try Inkblot’s new artificial intelligence platform that’ll help you stay in tune with an audience’s sensory symphonies: Perceivable Thresholds.

References:

Cian L, Krishna A, Elder RS. (2014). This logo moves me: dynamic imagery from static images. J Mark Res, 51:84-197.

Diano, M., Celeghin, A., Bagnis, A., & Tamietto, M. (2017). Amygdala Response to Emotional Stimuli without Awareness: Facts and Interpretations. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 2029.

Elder R.S., Krishna A. The effects of advertising copy on sensory thoughts and perceived taste. J. Consum. Res. 2010;36:748–756. doi: 10.1086/605327.

Engen T. (1988) Psychophysics. In: States of Brain and Mind. Readings from the Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Birkhäuser, Boston, MA.

Fechner, G. (1860). Elements of Psychophysics. Translated by Herbert Lanfeld. Rand, Benjamin (Ed.) (1912). The Classical Psychologists. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 562-572.

Krishna, A., Cian, L., & Sokolova, T. (2016). The power of sensory marketing in advertising. Current Opinion in Psychology, 10, 142–147

Vojtko, V. (2014). Rethinking the Concept of Just Noticeable Difference in Online Marketing. Acta Informatica Pragensia. 3(2). P. 205-216.

Webster M. A. (2012). Evolving concepts of sensory adaptation. F1000 biology reports, 4, 21.

Today, marketing and advertising are as much an art as they are a science.

The selective consumer engages with content based on more personalized psychological factors that can predispose them to seeing things in a certain...

Personality traits are stable, consistent characteristics of a person that are detectable in their actions, attitudes, and feelings.

Be the first to know about new psychological insights that can help you optimize customer touchpoints and drive business growth.