What Are the Most Common Criticisms of Projective Tests?

So what’s wrong with projective tests? Here are some of the top critiques.

As the inkblot test grew and developed, variations of the core idea formed.

During the Second World War, psychologists Molly Harrower-Erickson and Matilda Steiner modified the original Rorschach test for the purposes of screening large groups of participants for duty (i.e. military personnel) in a short period of time (Wittson et al., 1944, Rottersman, 1945, Springer, 1946). Harrower-Erickson’s innovative approach birthed new life to the Rorschach, creating two new forms of the inkblot test: large group inkblot tests and multiple-choice inkblot tests. However, the multiple choice method was found to be unsuitable in military practice, as the normal populations tended to score over the test’s proposed indicator for psychological disturbance, resulting in a lack of differentiation between normal and disturbed subjects (Wittson et al., 1944, Springer, 1946).

Funded by a grant from Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, Harrower-Erickson and Steiner developed the Rorschach group test in 1941, and published their initial findings in the 1943 paper titled, Modification of the Rorschach method for use as a group test. The modified procedure was defined as being distinct from the original/individual method as it varied on several levels. The unique selling point of the group test was that it reduced the administrative load of the test, which allowed the examiner to focus whole-heartedly on the scoring and interpretation. In the same issue (62) of The Journal of Genetic Psychology, Harrower-Erickson published the Directions for administration of the Rorschach group test.

Reproductions of the same ten traditional Rorschach cards—some black and white, some colored—were used. The inkblot slides were projected from “35mm roll film” onto a five by six foot screen in a darkened room, or the regular Rorschach cards could be used as well (Harrower-Erickson, 1943). The author stressed that the room must be dark, however the other details—like screen size and seating— were not fixed, and could bend to the needs of a given testing room. Harrower-Erickson reported a notable experiment, where the lights were turned off during the visual sequence and then turned on again during the recording sequence. Surprisingly, all of the subjects asked to participate entirely in the dark (Harrower-Erickson, 1943). Notably, however, the multiple-choice version of the test would be conducted in this manner (Harrower-Erickson and Steiner, 1945).

The subjects sat in the center of a room and faced the screen head on. Each slide was displayed for three minutes, and the subjects were instructed to write down their perceptions—what each inkblot “reminded you of, resemble, or might be,”—at their own pace in a “special booklet” that contained tuck away flaps (Harrower-Erickson, 1943 p. 108, Harrower-Erickson and Steiner, 1943, p. 120).

During the response phase, the subjects recorded what they saw in each card on a single page of the booklet. After completing the set of cards, the administrator instructed the subjects to view the left side of the hidden flap for the card in question. The left side of the flap contained a diagram of the inkblot. The administrator would then project a new, labeled version of a card on the projector and suggest commonly perceived forms in that particular inkblot slide. For example, in viewing a card in the series—which for example could have corresponded to the original Rorschach card I—a subject might have seen a butterfly, and then written that down as their answer (Harrower-Erickson, 1943). The subjects were then instructed to number their answers and then draw a line to the corresponding inkblot feature for each card in question. In short, the administrator needed to know what they saw and where they saw it (Harrower-Erickson, 1943).

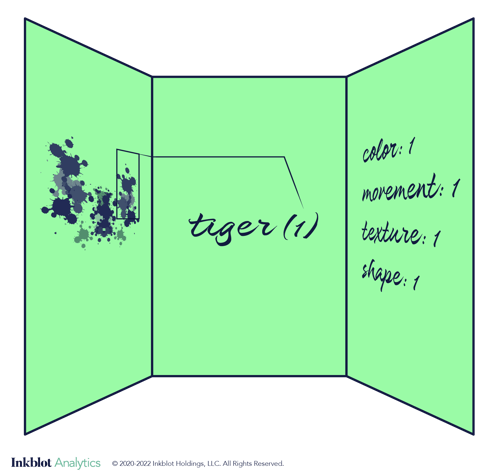

Next, the subjects were instructed to view the right side flap, which indicated the content analysis task incumbent upon the subjects. Specifically, the words “color, movement, texture, and shape” appeared on the right side flap (Harrower-Erickson and Steiner, 1943, p. 120 ). The experimenter explained that the subjects were to indicate the characteristic and experiential details of each card in question. For example, in viewing another card of the series—which for example could have corresponded to the original Rorschach card VIII—the subject might have seen a tiger, written that down as a response, and then numbered it (1) per the prior instructions. However in their mind’s eye, the pink, furry tiger appeared to be walking by a river. Therefore in this secondary coding phase, the subject was instructed to label those attributes, should they have truly seen such accessory details (Harrower-Erickson, 1943). After these instructions were given the slides in question were projected in the same order and displayed for about two minutes.

Take the case of the tiger in the visual example below:

Since the object in the slide was seen: in a specific color (pink), as performing an action (walking), as having a quality of appearance (furry), and as a particular form (tiger), the subject would label the (1) by each word, and so on and so forth through the rest of the cards in question. The results were then scored according to Rorschach’s aesthetic language of abbreviations, like movement, color, and form. Therefore a person with prior Rorschach training would better intuit the scoring method (Harrower-Erickson, 1943).

Harrower-Erickson and Steiner were not the only researchers who sought to modify the Rorschach for large scale purposes. Psychologist Marguerite Hertz released her method in the 1943 paper, Modification of the Rorschach inkblot test for large scale application. Hertz, in association with the Brush Foundation, proposed their own methodology to “improve the technical aspects of the group method,” (Hertz, 1943, p. 191). For example, they found that spoken instructions were insufficient, and written directions were a necessary accompaniment. Even more notable, Hertz reported that subjects often noticed and reported “figures within the blots in the photographs which they did not notice in the slides.” (Hertz, 1943, p. 192)

Harrower-Erickson and Steiner continued to innovate the Rorschach. The group test had succeeded in cutting the administration and interpretation. However, the two contended that because the Rorschach test still required extensive training to interpret, it was not a traditional psychological test in the psychometric sense (Harrower-Erickson and Steiner, 1945). The psychologists decided to build upon a prior inkblot multiple choice test created by Lewis Terman in 1936 (Terman and Miles, 1936).

Unlike the original group method, the restriction of response in the multiple choice format changed the nature of the procedure—meaning that the new multiple choice Rorschach was “an entirely different procedure, rather than a further modification of Rorschach's method,” (Harrower-Erickson and Steiner, 1945, p. 331). Hence, the multiple choice Rorschach could be classified as an objective test, in the sense that it contains a defined set of responses to the task, where the items are predetermined by scale. Their underlying assumption was that responses individuals would give in an open response Rorschach would be similar to those in the multiple choice (Harrower-Erickson and Steiner, 1945).

The test can be administered in large groups, to an individual, and even as a self-administered test. This flexibility was a key aspect of the test’s attractiveness to the military, who needed to perform rapid screening in the Second World War.

The subject(s) would be shown each of the ten inkblots, one at a time, in a similar fashion to the group procedure (i.e. projected in a darkened room). The subjects would then choose from a list of ten multiple choice options—five of which were options regularly chosen by normal individuals and five of which were options indicative of those with psychological disturbances—that they felt best described the inkblot in question (Harrower-Erickson and Steiner, 1945). Subjects were allowed to make up to two choices, or none at all. In terms of scoring, the weight was placed on the first score, especially if the purpose of the test was for quick evaluation.

Ironically, the procedure was conducted in the “lights off, lights on” manner during the viewing and recording phases, which was found to be the non-preferred procedure for the original group test.

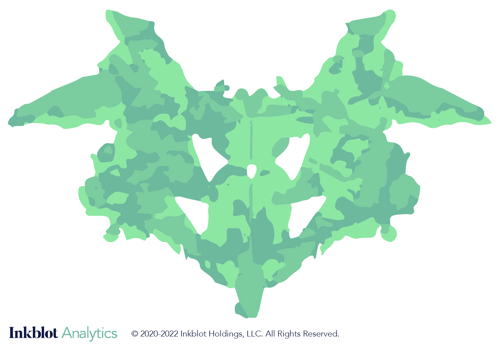

Suppose that you are taking the multiple choice Rorschach test. After receiving the instructions, you are shown the first card of the series, which happens to correspond to Rorschach card I (see below for example).

After viewing the card for the allotted time, you are prompted with the following list of options, from which you are directed to choose which option best describes the blot, a secondary descriptor, or none at all:

□ An army or navy emblem

□ Mud and dirt

□ A bat

□ Nothing at all

□ A pelvis

□ An x-ray picture

□ Pincers of a crab

□ A dirty mess

□ Part of my body

□ Something other than above: ______________________

(Harrower-Erickson and Steiner, 1945, p. 332).

As detailed by Captain Wiliam Rottersman, “a key is provided for the answers; one number from 1 to 10 is given for each answer. Those answers with key numbers 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5 are considered satisfactory answers; those with 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 unsatisfactory. The number 10 answer for each card is nothing at all, (Rottersman, 1945, p. 501).

The authors wrote that a score of four or more unsatisfactory answers (i.e., answers that correspond to the norms of disturbed samples) is an indicator for further screening due to presence of psychological disturbance, however this is not a rule set in stone. Rather, Harrower-Erickson and Steiner elaborated that this number was settled on empirically as the ideal indicator for the groups they tested (1945). They concluded that a proctor—if they wish to simply select the best candidates and screen the most disturbed—could use five or six unsatisfactory answers as a criterion for screening, and zero or one unsatisfactory answers as a criterion for selection (Harrower-Erickson and Steiner, 1945).

If you are interested in taking the entire Harrower-Erickson multiple choice Rorschach test, you can do so on the website openpsychometrics.org, an open source psychometrics project.

References:

Harrower-Erickson, M., & Steiner, M. E. (1943). Modification of the Rorschach method for use as a group test. Pedagogical Seminary and Journal of Genetic Psychology, 62, 119.

Harrower-Erickson, M. (1943). Directions for Administration of the Rorschach Group-Test, The Pedagogical Seminary and Journal of Genetic Psychology, 62:1, 105-117.

Harrower-Erickson, M., & Steiner, M. E. (1945). The Multiple Choice Test for Screening Purposes. In M. R. Harrower-Erickson & M. E. Steiner, Large scale Rorschach techniques: A manual for the group Rorschach and Multiple Choice Test. 331-341.

Hertz, M. R. (1943). Modification of the Rorschach inkblot test for large scale application. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 13(2), 191–211.

Lt. Comdr. C.L. Wittson (M.C.) U. S. N. R., Lt. Comdr. W.A. Hunt H-V(S) U. S. N. R. & Lt. (JG) H.J. Older H-V(S) U. S. N. R. (1944). The Use of the Multiple Choice Group Rorschach Test in Military Screening, The Journal of Psychology, 17:1, 91-94.

N. Norton Springer (1946) The Validity of the Multiple Choice Group Rorschach test in the Screening of Naval Personnel, The Journal of General Psychology, 35:1, 27-32.

Rottersman, W., Goldstein, H. (1945). Group analysis utilizing the Harrower-Erickson Rorschach test. American Journal of Psychiatry. 101:4, 501-503.

Terman, L., Miles, C. C. (1936). Sex and Personality. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York.

So what’s wrong with projective tests? Here are some of the top critiques.

After Hermann Rorschach’s sudden death in 1922, his inkblot test began to take on a life of its own as it traveled around the world.

Recently the Rorschach test has seen another revival in media headlines.

Be the first to know about new psychological insights that can help you optimize customer touchpoints and drive business growth.